HouseWork(s)

Artist’s Statement

HouseWork(s) presents work from the past decade of my practice – bringing solitary and private practices into conversation with collaborative and public projects. As an interdisciplinary artist who works both inside of and far afield from the “studio” and the gallery, I engage with art-making as a research practice and as an intervention – as a way to examine, discover and reveal something about the world and to open a space for dialogue within it.

My solitary practices serve as both conceptual and material research – as ways of finding and figuring out how to make my questions and concerns visible and how and where to bring them into encounter with others. My collaborative and socially-engaged projects invite others into the process, acknowledging that at least some of what I long to make or make visible, cannot be done alone. Working with others and sometimes about and alongside others, I am interested in how we inhabit our place, how we work within it and how we know it.

The preoccupations I have been exploring in the last ten years remain rooted in longstanding concerns about embodied labour and “women’s work,” everyday contemplative rituals, local knowledge and the construction of community. Most of the work in HouseWork(s) has been exhibited or undertaken in other locations – in galleries or artist-run centres in Canada or the U.S., and in non-art spaces in Newfoundland that include a bakery, a fish-processing plant, public libraries and a range of community spaces in Bonne Bay and the Great Northern Peninsula. It is a great pleasure to share this work with audiences at The Rooms in St. John’s.

— Pam Hall, 2014

The texts below are excerpted from the catalogue essay for Pam Hall: HouseWork(s), by Melinda Pinfold, PhD.

The History House

- The History House in Kamloops.

- The History House in Kamloops.

- The History House, at Kamloops Art Gallery (2015).

In 2004, Hall began an ongoing visual dialogue and four-year long collaboration entitled Marginalia with Vancouver performance artist, Margaret Dragu. An extended, bi-coastal conversation was made visible through the daily making and sharing, by each artist, of a soft and sometimes ragged “memory cloth.” During the period of the collaboration, Dragu and Hall each produced, every day, a 30.5 × 30.5 cm cloth work. Each memory cloth is then, roughly, one-foot square. This measure is only approximate, and it was chosen as suggestive of the natural measure of the human foot used in marking out distances. Step by step, day-by- day, through their work on the cloth carres, Dragu and Hall “moved closer,” metaphorically, to each other despite the enormous geographic expanse that separated them. The techniques employed by the artists included (and subverted) the more traditionally female domestic skills of sewing, ironing, embroidering, and appliqué/collage.

The History House, exhibited in HouseWork(s), is one small echo of Hall’s side of this collaborative ‘conversation,’ this “soft history.” Exhibited now at The Rooms, The History House has become the emissary for the much larger project of Marginalia, where it was first exhibited in 2008.

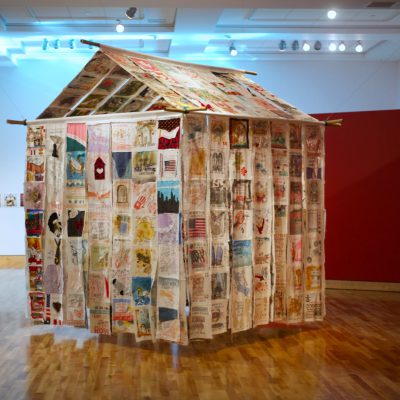

The Work House

The Work House (2014), which is related to the Dressing Up Work series in HouseWork(s), was completed in the gallery, during the first two weeks of the exhibition. During the performance, Building the Work House, three women artists sewed, for four hours a day, silently fabricating the apron panels for this house. The hundreds of colourful and varied aprons that make up this house were either collected by the artist, or sent to her from women around the country. Many of these aprons are handmade, and they point nostalgically to a time and a sensibility when, after the housekeeping efforts of each day, mothers and wives would “freshen up” by changing into a gay, clean apron at dinnertime.

For its duration, the 40-hour performance inhabited and dominated the otherwise orderly space of the gallery. It confronted the exhibition’s system. The women’s work was made visible; the riot of piled aprons was stitched and structured into the vertical panels that would become the ‘walls’ and ‘roof’ of the final five-pole house in the exhibition. When it was completed and installed, The Work House introduced an undeniably female presence into the gallery. The gaily-coloured aprons of the exterior house a complex, soft, diaphanous and more-pastel interior. The languid weight of the aprons that form this house muffle the noise of the outside world. The inside of The Work House is a safe space; quiet and contemplative – laboured yet luminous. A celebration of all the work of all the women.

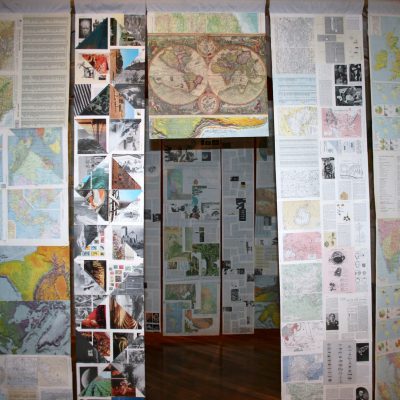

The Knowledge House

The Knowledge House (2014), another of the five-pole houses that anchor this exhibition, addresses in part the problems of what it is that we think we know, how this “knowledge” is formulated, and how it is presented to us for use or retrieval. Typically, an encyclopedia is understood to offer comprehensive, universal knowledge. Its series of volumes are, generally, arranged either alphabetically or thematically. In the deconstruction and the removal of numerous pages from vintage encyclopedias and atlases, and then recombining them in what seems at first to be an ad hoc manner, Hall coaxes us to consider new associations, informational alliances, and meaning pathways. The artist thus furthers a disruptive process of linguistic ambiguation. In the probing physicality of the stitching – the repetitive penetration of the machine’s needle, the threads that tether each of the pages together – the panels of this house metaphorically key us to the ways we make connections.

Towards A Newfoundland House of Prayer

- The Newfoundland House of Prayer, 2014

- Detail

- Detail

- The Providence Prayer Blanket, 2014

- Detail (Providence Prayer Blanket)

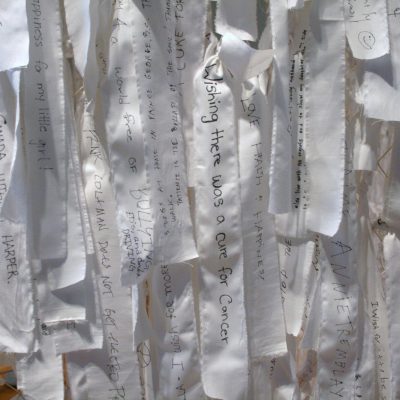

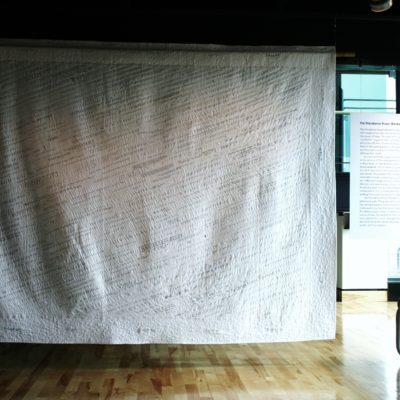

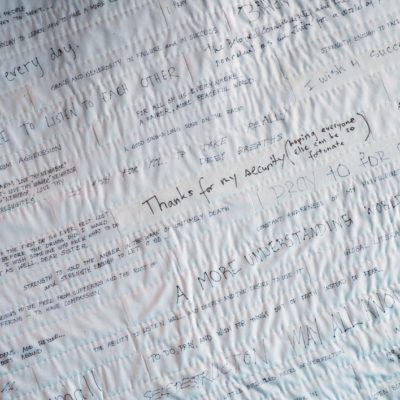

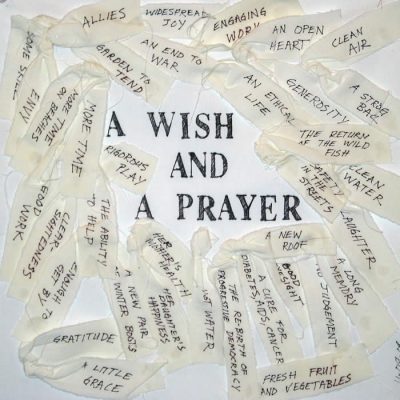

The heart of the larger five-pole house that is Towards a Newfoundland House of Prayer (2013-2014) is a hand-wrought twine net, fabricated by Eric Snelgrove, a retired fisher. Individual wishing walls for the House were displayed, throughout about a year, in various public places in locations in St. John’s, Stephenville and Corner Brook. Wishes were also solicited from further afield. Anyone who wished was invited to write a prayer or a desire on a strip of cotton, and affix it to the netting. The result is the light-filled and ethereal large-scale prayer house. Its net roof is open to the light, and smooth sea rocks and twine are employed to tether this airy structure within the confines of the gallery. The elements of this house shift slightly in the ambient breezes in the gallery. Their movements echo the just audible sounds of murmured prayers.

Towards a Newfoundland House of Prayer is one of the most visually subdued and monochromatic works in the exhibition. But this house, covered as it is with wishing rags and prayers, physically brings to form, makes visible our human hopes and aspirations. This house is like a choir, and its fluttering white rags hold, and give voice to, our wishes and our desires. With 32 Days Towards a House of Prayer, Towards a Newfoundland House of Prayer and The Providence Prayer Blanket, our litanies of hope and longing are made real, exposed, ragged and raw. Through these works, we may find community and a knowledge that we are trusting in that which is at once within us and yet beyond us.

Housing Knowledge

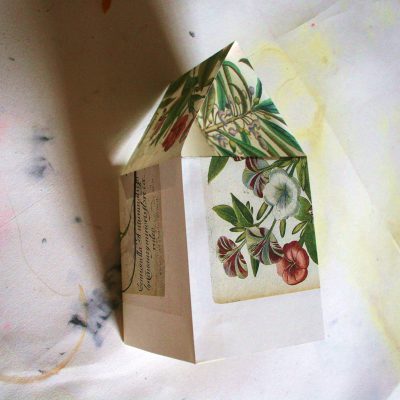

In tandem, somewhat, with the Building a Village collaborative project, and in direct ‘conversation’ with the five-pole Knowledge House, Hall constructed a series of folded “houses” utilizing the lush imagery of vintage botanical reference books. The artist photographed the completed houses in varying light conditions and angles. The five photographic images in this section of the gallery are selections Hall made from among the larger group. In each case, the house that served as subject for the large photographic image is mounted on a shelf before its own image, thus it is in dialogue with itself. The question of who is the observer and who is the observed becomes even more vexed as the gallery viewer’s own reflection in the glass of each photograph “looks back” at him or her, and enters into the conversation of a dialogic space.

Hall describes the small, folded houses in Housing Knowledge as “both working objects and studies in both real and symbolic illumination.”The houses are staged to capture daylight (day’s light as unfettered illumination, and thus, truth) within their interiors. For Hall, the tiny houses, and their larger scale photographic “portraits,” allude to the “enlightenment” that we demand of knowledge.

Small Gestures

Since 2009, Hall’s daily practice has taken the form of Small Gestures, humble actions undertaken each morning as calls to attentive presence. These performative-action-gestures remain the artist’s ways of paying close attention, of stepping toward mindfulness, and of enacting an awakened gratitude for everyday wonder. Hall, who is an accomplished writer and crafty wordsmith, often includes text with the images that she shares each day on Facebook. Hall’s Small Gestures may be pithy or provocative, but they are always downright beautiful, and that is enough. In HouseWork(s), a long phrase of Small Gestures in the form of houses was the first imagery to greet visitors. Over the years of that humble daily practice, the form of the house recurred, returned, and echoed across sites and spaces and across time.

HomeWork: Doing the Math

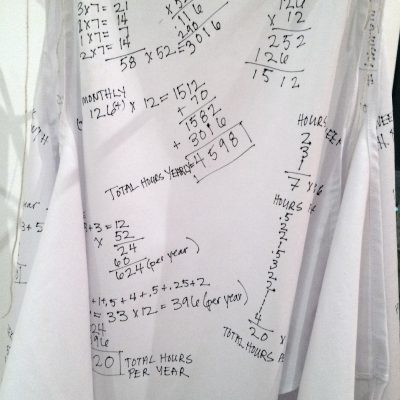

When HouseWork(s) travelled to the Kamloops Art Gallery in 2015, Hall added a new performance piece that incorporated the “story aprons” from Auntie Crae’s in St. John’s, and the questions counting hours of housework for the work portraits from Arnold’s Cove. Using long commercial aprons, Hall inscribed the working hours of audience members who filled out questionnaires adding up the hours they spent on ordinary “housework”. Ironing, shopping, cleaning, and childcare were some of the categories participants counted , and passed to Hall, who inscribed them with care on blank white aprons and “did the math” standing at an ironing board in the gallery for 6 hours. When she was finished, a new “workhouse” had been created that, in its own mysterious numerology, revealed some of the layers of labour — conceptual, physical and emotional — that we invest, without noting, every day.